Grow something a long time and it gets big, like elms in The Oval. Broad and strong, enhancing the land all around. But in time, big things can become vulnerable; stressors press in and threats emerge. It can happen to a tree or a person, a building or an institution.

And so it is with the modern research university.

Building blocks of society, America’s research universities have churned out inventions such as the internet, weapons such as the atomic bomb, technologies such as recombinant DNA, and medicines to treat cancer. Advances we scarcely notice, such as X-rays, sensors, and antibiotics, benefit everyone. Scholarship and discovery, in concert with government power and industry scale, turned the United States into a superpower, building a technology-based global economy that competitors strive to match.

Add Colorado State University, a research epicenter of the Mountain West. Ranked among the best research universities in the country, CSU is a leader in infectious disease prevention, veterinary medicine, natural resources protection, sustainability, and atmospheric science. Moreover, the land-grant mission means CSU operates like a conveyor belt, assembling practical knowledge like widgets for export across Colorado and beyond.

Established for more than 150 years, the University’s success seems ordained.

Yet, beyond CSU’s leafy trees and lush lawns loom big challenges as well as opportunities. Powerful forces are reshaping U.S. research universities in the form of competition, cultural change, and economic and political pressures. Each challenge presents risk as well as a way to grow the University’s research enterprise. The coming decade will be a test of resiliency.

CSU’s Surging Research Enterprise

Plant a seed, care for it long enough, and something wonderful will grow. In effect, that’s what President Lincoln and Congress did when the Morrill Act of 1862 created the first land-grant universities, which led to CSU’s establishment in 1870. Since, the University has emerged as a research force on a scale scarcely imagined then. Its growth lifted communities in Northern Colorado and contributed to a flourishing economy on the Front Range.

The United States has 146 tier-one (R1) doctoral degree research universities, including Johns Hopkins University, Stanford, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and UCLA. Within this exclusive club, CSU ranks number 65, according to data kept by the National Science Foundation and Carnegie Classification of Higher Education Institutions.

CSU may lack the prestige of big universities on the East or West coasts, but the ambition is quite alive.

“We always have to aspire to the next level. We have to be resilient and flexible and adaptive to new situations,” said Alonso Aguirre, dean of the Warner College of Natural Resources. “We need to be a magnet for students, faculty, grants, and media coverage so we can grow our prestige.”

Today, CSU’s research reach extends around the world. There are scientists who have studied diseased deer in Norway, bats in Uganda, cookstoves in Guatemala, and bioluminescence in oceans near Indonesia. CSU researchers help put satellites in space, catalog the microscopic world of air we breathe, pursue next-generation fuels, and stop pathogens that kill people.

In climate research, CSU is part of a first-of-its-kind $160 million National Science Foundation Regional Innovation Engine proposal, a major public-private partnership. NASA and CSU have embarked on a $177 million project to study tropical storms, called Investigation of Convective Updrafts. And the Department of Energy supports research to cut emissions of methane, a potent greenhouse gas.

In energy, a newly installed 3.5-megawatt industrial turbine generator at the Powerhouse Energy Campus will advance research on low-carbon power generation. CSU is part of a consortium vying for a Western interstate hydrogen energy hub with funds from the Biden administration. The Energy Institute has emerged as a leader in research on low-carbon fuel alternatives for Colorado and the country.

In sustainable agriculture, CSU launched a new Soil Carbon Solutions Center to find ways to store carbon in earth to benefit agriculture and reduce greenhouse gases. An international coalition, co-led by CSU, announced a $19 million project to study how rangeland management affects soil health. The College of Agricultural Sciences launched six new research projects under the Nutrien-funded Solutions to Colorado Commodity Challenges program. And AgNEXT, now in its third year, added more researchers to study ways to make animal agriculture safe for consumers and ecosystems.

Janet McCabe, EPA deputy administrator, learns about AgNext and CSU agricultural research at the Agricultural Research, Development, and Education Center. Credit: John Eisele, CSU PhotographyIn public health, CSU researchers are part of a $12.5 million, NSF-supported institute that will advance research and education to prevent viruses transmitting from animals to humans. CSU experts developed a machine, VacciRAPTOR, a rapid-tester for vaccines and a quicker path toward clinical trials. The Columbine Health Systems Center for Healthy Aging launched the Colorado Longitudinal Study, which will create a unique biobank from 1 million Coloradans over the next 10 years to predict health outcomes. And the University earned wide praise for its leadership during the COVID-19 pandemic due to its efforts to protect people in Colorado nursing homes and students.

CSU is one of the nation’s top producers of Fulbright U.S. Scholars — professionals, artists, and scholars who usually hold faculty appointments — according to a report published in The Chronicle of Higher Education. The University boasts the nation’s second-ranked veterinary college and the best sustainability program of any American university and is a national leader in atmospheric science. It is ranked among the best places to work in Colorado, to boot.

Big challenges lie ahead for the University’s research enterprise. Change is reshaping the research university landscape.

Last year, CSU reported a record-breaking $456.9 million in sponsored projects expenditures, chiefly for research. That was up about $10 million from the previous record of $447.2 million, which had eclipsed the year before (2019-2020) by 10%. In the past 10 years, research expenditures have increased 46%.

If success begets success, it would seem that CSU could soon vault into the top echelon of America’s elite research universities. But that is far from assured.

The elite institutions atop the hierarchy are growing much faster, widening the gulf between themselves and the rest. CSU finds itself at an inflection point.

The Big Get Bigger

To appreciate the challenge facing CSU, imagine the top-tier U.S. research universities are fish in a pond.

Every day, someone feeds the fish and they grow – but at different rates. Some fish get fed much more than the others, so they grow to enormous proportions and consume more and more food to sustain their mass. Meanwhile, the rest of the fish, the vast majority, compete for less and less food, and they grow slower, if at all.

Consequently, big research institutions gobble more funds, faculty, and corporate partners. It’s a consolidation of giants at the top of the food chain, at the expense of the rest. CSU will have to adapt to these conditions to expand research.

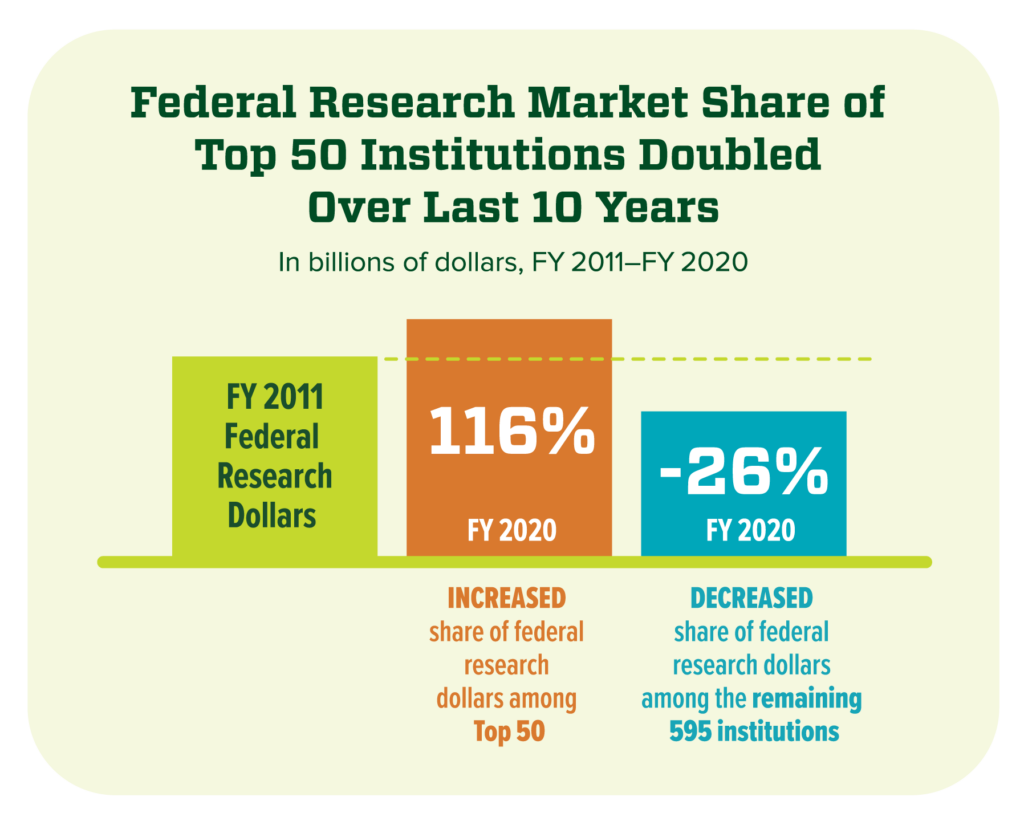

Over the last 10 years, the share of federal research dollars going to the top 50 research institutions – those just ahead of CSU in the rankings – more than doubled while the amount for the rest fell by 26%. Today, just 19 of the top 50 universities spend more than $1 billion each on research annually. Among them: University of Pennsylvania; University of California-San Francisco; Harvard; University of Michigan-Ann Arbor; UCLA; University of Washington; UC San Diego; Cornell; Yale; University of Wisconsin-Madison; Duke; Columbia University; Arizona State University; and University of Texas-Austin.

The findings are contained in a series of reports that EAB, a Washington, D.C.-based consulting firm, prepared for the CSU Office of the Vice President for Research.

The top 50 U.S. research universities capture more than twice as many federal research funds today as they did a decade ago. Meanwhile, the remaining universities captured 26% less than a decade ago.

Source: Higher Education Research and Development survey, FY2011–FY2020; EAB.

Credit: Wendy Brookshire, CSU Marketing & Brand ManagementCSU’s sponsored project expenditures, most of which are for research, have increased 46% in 10 years – a rate comparable to peer institutions such as Virginia Tech, Iowa State University, University of Illinois, and Purdue University. During that period, the OVPR has more than doubled the number of centers and institutes, including the Center for Healthy Aging, One Health Institute, and Data Science Research Institute – units organized around interdisciplinary team science. The Catalyst for Innovative Partnerships program seeded efforts such as the Partnership for Climate and Health, Soil Carbon Solutions Center, B-Sharp and Mental Wellness, Rural Wealth Creation, Food Systems and Security, and Climate Adaptation Partnership. CSU now has many diverse and interdisciplinary research endeavors. It has been a busy season indeed.

But despite the gains, CSU has a big competitive disadvantage; it lags far behind its peers in institutional support. In 2020, institutional expenditures for CSU research were only 15% – less than half the portion provided to peer institutions.

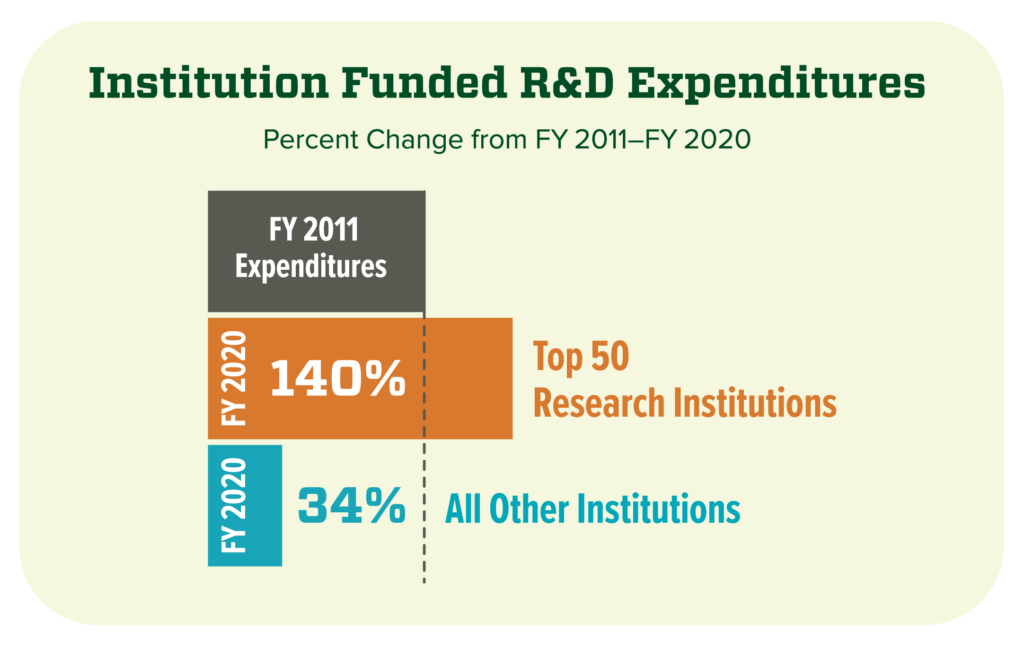

The situation is even more stark when compared to the top 50 research universities. They increased their institutional research expenditures 140% in the past decade, whereas the rest of the research universities averaged about 34%, the EAB reports show. The disparity underscores how continued success requires substantial internal investment.

Institution-funded research expenditures at the top 50 research universities increased 140% in the past 10 years, compared to a 34% increase at all other institutions.

Source: Higher Education Research and Development survey, FY2011–FY2020; EAB.

Credit: Wendy Brookshire, CSU Marketing & Brand ManagementWorse yet, CSU corporate support for research is about 7% of total award obligations, whereas other institutions receive about 35% to 50%, according to officials at the OVPR.

Other challenges loom.

For example, the boomtimes of pandemic-related funding are ending, and a more resource-constrained environment will emerge as universities adapt to federal expenditures returning to pre-pandemic levels.

Political and economic turbulence will complicate the path forward too. Inflation and competition cause soaring prices for faculty, facilities, equipment, and construction. Consider a proposed bat research facility at CSU, funded in part by $6.7 million from the NIH. The project costs have risen to $10 million before groundbreaking commences this summer.

A divided Congress and populist politics increasingly challenge elite institutions as well as scientific integrity. The 2022 midterm elections resulted in new calls to limit federal spending and lower the national debt ceiling, which would affect research funding. Meanwhile, many people openly question the value of higher education. Such political crosswinds increasingly cause friction between university leadership, faculty, and governing boards.

“The perception of some people is they don’t trust science. But if people don’t trust science, they can make bad decisions for themselves and their community, as we saw during the pandemic,” said Barbara Snyder, president of the Association of American Universities and member of a newly formed National Academy of Sciences committee called the Strategic Council for Research Excellence, Integrity, and Trust.

There are other challenges too. For example, competitive salaries vex CSU given the need to attract and retain faculty and staff in relatively high-priced Fort Collins. Improved donor relations are important to grow revenue. And faculty and graduate student researchers need more building space for labs and research centers. Not surprisingly, these are among priorities for the University, identified by CSU President Amy Parsons and the Board of Governors.

At a crossroads, the path ahead will shape more than the University’s research enterprise. It will determine its brand and identity in the marketplace of higher education.

A Changed Landscape

To go someplace you’ve never been before requires taking a new course. Or one might get there by following those who have gone before. Either way, a new venture awaits.

In the past, the blueprint for building a research university was simple: Hire bright people; pursue research grants; ignore competitors; and assume money would flow to established programs.

But it doesn’t work that way today. The top research universities are using a different playbook; if CSU seeks to gain the next level, it will need to account for an increasingly competitive landscape.

Today, the elite research universities focus on a few core areas in which they have distinct competitive advantage. They partner with big corporations to share ideas and scale solutions. They invest in core facilities and research infrastructure. They concentrate on federal spending skewed toward defense and health sciences. They poach talent. They expand online master’s degree programs and relentlessly reinvest revenues in research. And they benefit from surging institutional funding, EAB’s findings show.

Horses are evaluated and treated at the Johnson Family Equine Hospital at Colorado State University. Credit: John Eisele, CSU PhotographyIndeed, some of CSU’s peers are preparing to take the next leap with bold ventures. Virginia Tech is stitching together a medical school, a veterinary school, and three biomedical institutions. North Carolina State University’s Centennial Campus includes big corporate partners such as GSK, Adrenas Therapeutics, and Merck. The University of Illinois’ iMBA program is among the most popular of its kind in the world. And Purdue’s Global Campus was created through the acquisition of for-profit Kaplan University.

So-called grand challenges represent new ways universities concentrate scholarly might to achieve practical solutions to societal problems. UCLA launched two grand challenges – one to respond to depression and mental wellness, the other to transform Los Angeles into the world’s most sustainable megacity by 2050. A Washington State University grand challenge combines research strengths in veterinary medicine, agriculture, and engineering to study functional genomics, health disparities, and water availability.

Indeed, CSU has done well securing federal funding for research; last year, the University’s federal expenditures for research totaled about 73%, better than many peer institutions.

By consolidating resources and concentrating on core strengths, the top research universities increase their appeal to federal funding agencies, including the NSF, NIH, and Department of Defense. For those agencies, sending dollars to the wealthiest and most successful schools yields better results and involves fewer political squabbles and submissions and awards to administer. In turn, those measures attract donors and businesses, so top-tier research universities grow even bigger. They can spend more on superstar faculty and postdocs, pay legal fees to settle lawsuits over poaching, and compete with international universities splashing big money to attract American scholars, such as Mexico’s Monterrey Institute of Technology, which budgeted $100 million to lure prominent scholars south. In the resource-constrained environment ahead, big funders prefer to work with research universities that can make the most of limited funding and apply their efforts toward societal problems, according to EAB.

They build shiny new buildings such as the University of British Columbia’s $140 million Biomedical Engineering Building or the University of Hawaii’s $65 million Life Sciences Building. They invest in cutting-edge innovation projects, such as the $100 million Pennovation Center at U-Penn, which added a $365 million industry incubator. The University of Michigan and Ford partnered to invest $75 million in a robotics facility and extend education and training to local schools and colleges. ASU partnered with Blue Origin to build a business park in orbit, staking a claim in space-based research.

This is how the R1 research universities just ahead of CSU ascend to the top of the food chain and grow to gargantuan proportions. As resources across the board tighten, funders seek to work with institutions that can make the most of limited dollars and apply their efforts toward concentrated problems.

CSU Inflection Point

The good news is CSU is beginning to pursue similar approaches.

For example, in a landmark agreement, Zoetis, the world’s leading animal health company, established a 3,000-square-foot research lab at the CSU Foothills Campus to explore the livestock immune systems and target new immunotherapies. Some 40 University and company researchers collaborate, intending to find alternatives to antibiotics in food-producing animals. The emergent bioscience industry on the Front Range appealed to the company.

CSU has a proven track record of collaboration with other universities, federal labs, investors, and companies in Colorado. It plays a leadership role in catalyzing a robust technology innovation ecosystem that propels a rapid economic transformation on the Front Range. Credit a highly educated workforce, clusters of universities and federal labs, and a can-do spirit of entrepreneurialism embedded in the culture of the Mountain West. Moreover, the University’s land-grant mission mandates that the University apply knowledge for practical solutions across Colorado.

“The pioneering culture of the region is palpable,” said CSU Vice President for Research Alan Rudolph. “This is a culture that grew up knowing if we didn’t work together, we wouldn’t thrive. The culture of innovation is embedded in who we are in the region.”

CSU laser lab. Credit: John Cline, CSU Office of the Vice President for ResearchCSU’s most ambitious research endeavor is found in a bold, new proposal to attract millions in federal dollars in search of climate change solutions for the region. The Colorado-Wyoming Innovation Engine proposal coalesces powerful interests to respond to the climate crisis. Specifically, the plan is to create a “hub-and-spokes” model converging government power, business investment, and higher education smarts to develop new tools and techniques to monitor climate change and mitigate impacts on water resources and environmental and economic threats. It would help empower local communities to build a more resilient regional economy and protect public health and property. Unprecedented in scale, the proposal would join two states, four research universities including CSU, five other higher education institutions, eight corporations, and six government laboratories along the Front Range. At stake is $160 million from the NSF over 10 years. A decision is expected before Oct. 1.

Indeed, CSU has done well securing federal funding for research; last year, the University’s federal expenditures for research totaled about 73%, better than many peer institutions.

Elsewhere, the University’s investment in the Research and Scholarship Success Initiative helped seed key research initiatives, including the Catalyst for Innovative Partnerships program, research centers and institutes managed by the OVPR, and core facilities serving researchers across CSU. The initiative also supported research safety training, regulatory compliance, and COVID-19 response actions. The five-year, $5 million initiative began in 2018.

At the Energy Institute, researchers collaborate with Caterpillar Inc. and Cummins Inc. to advance clean energy. The College of Agricultural Sciences partners with the Nutrien company, the world’s largest provider of crop nutrients, inputs, and services, on research into modern agriculture and meeting the challenges of food safety and security.

CSU STRATA helps faculty, staff, and students bring their intellectual property and innovations to marketplace, among other services. It connects the CSU System community with industry leaders and world-class innovators. (CSU STRATA is the new company name representing the joined services of CSU Ventures and the CSU Research Foundation). Last year, STRATA reported 32 licenses, 71 invention disclosures, and 157 intellectual property applications.

And the newly launched CSU Spur campus, a partnership between the CSU System and the city and county of Denver, connects the University’s education, research, and outreach missions to the community. It features interactive exhibits, K-12 outreach, adult learning opportunities, and research in three buildings: Vida, dedicated to human and animal health; Terra, illustrating CSU’s excellence in agricultural service to Colorado; and Hydro, addressing the state’s critical water challenges and resources and developing solutions.

Rebekah Kading, assistant professor of microbiology, immunology, and pathology, is working on a vaccine for Rift Valley fever, a virus transmitted by mosquitos. Credit: John Eisele, CSU PhotographyBut will those efforts be enough to propel CSU to the next level of research universities? Will they help prepare the University for the competitive marketplace ahead?

“Colorado State University is well-poised among the upper echelon of R1 universities and really stands as a model for many public land-grant institutions seeking to do good while doing well,” said Jonathan Barnhart, director and senior consultant at EAB. “The challenge and the opportunity for a school like CSU is in its breadth and scale of activities.

“Research universities the size of CSU are good at a wide variety of things. And frankly, they’re probably great at a decent number of things,” Barnhart explained. “But the challenge for research universities of this size is in identifying what they are truly best at, what are the areas that truly differentiate your University from others. This could be in a particular academic discipline or an area of interdisciplinary research. This could be in geography or an area of service the University delivers better than anyone else. Identifying, and then building strategies, initiatives, and branding around those areas of unique value is how the top universities are going to truly separate themselves from another and compete in this resource-constrained, fast-moving environment,” he said.

CSU’s resolve for research – its very resilience – will be tested in coming years as change reshapes the landscape of research institutions from coast to coast. An existential test no less than the University’s identity hangs in the balance.

One big advantage for CSU is new leadership. Virtually the entire executive leadership team at CSU’s flagship campus in Fort Collins will turn over this year. It began Feb. 1 with the arrival of President Amy Parsons. Meanwhile, the vice president for research position becomes vacant after July 1; a national search is underway. It’s an extraordinary opportunity for new leaders to chart the future of CSU research, working with Chancellor Tony Frank and the Board of Governors.

Said professor Ken Reardon, associate dean for research at the Walter Scott, Jr. College of Engineering: “We need an understanding that investing in research is investing in the entire institution because it affects our reputation and brand and it influences why people come here for their education, even if they’re not aware of it.”

Gary Polakovic is the director of research communications for the Office of the Vice President for Research at Colorado State University and the editor for RESEARCH magazine.